The Musical Community of Gainsborough’s Portrait of Sancho

By Rebecca Cypess

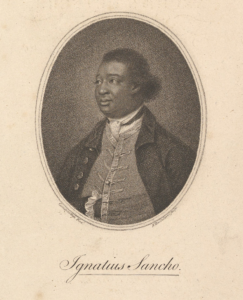

Discussions of Thomas Gainsborough’s portrait of Ignatius Sancho have understandably focused on the painting’s distinctive status as one of the few eighteenth-century British portraits to depict a Black man with such deep insight into his humanity and his character. (An image of the original is linked above, while the engraving based upon it, by Francesco Bartolozzi, appears as Figure 1.)

The engraving appeared in the posthumous collection Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African.

In contrast to portraits in which an enslaved Black or a Black servant—often a child—appears as a status symbol to project the power of a white sitter, Gainsborough’s portrait focuses exclusively on Sancho as a subject. And, unlike the surviving portrait of Francis Williams, another Black man whose education and social success may have been fostered by the Montagu family, the Gainsborough portrait is defined not by the external markers of erudition that surround him, but by a deep insight into Sancho’s character, with all its wit and skepticism. Indeed, a number of scholars have discussed the beauty and depth of the Gainsborough portrait by situating it within the practices of portraiture of Black people in eighteenth-century British art.

As a long-time resident of the fashionable spa town of Bath, Gainsborough came into contact with some Britian’s social elite as well as many leading artists, writers, and musicians. It was while the Montagu family was staying in Bath in 1768 that Gainsborough painted a portrait of the Duke and Duchess of Montagu, and it is likely that they commissioned and paid for the portrait of Sancho, as well.

At the same time, Gainsborough’s portrait warrants consideration in light of Gainsborough’s involvement in British musical life and his status as a musician himself. He played—or at least dabbled in—an impressive number of instruments, including violin, guitar, harpsichord, flute, viola da gamba, oboe, and bassoon. Books, articles, and museum exhibitions have been devoted to Gainsborough’s portraits of musicians, but, to the best of my knowledge, none of these has considered the Sancho portrait. By 1768, Sancho was already a published composer—a fact that he or the Duke and Duchess of Montagu would probably have shared with the famously musical Gainsborough.42

The original portrait is in private hands.

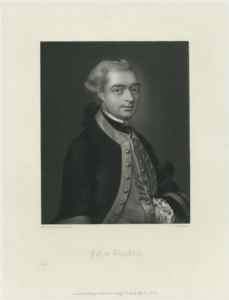

The objection might be raised that the Sancho portrait does not depict its subject with an instrument or musical score to denote his musicianship. It is true that many of Gainsborough’s musical portraits use such props, but this is not universally true. For example, his portrait of the violinist and composer Felice Giardini (Figure 2), a violinist with whom Sancho became friends, depicts Giardini without an instrument; in fact, Giardini’s pose is very much like Sancho’s, although his eyes engage the viewer directly, while Sancho’s look off to the side. Giardini’s expression bears a warmth and humanity that likewise mirrors that of Sancho in Gainsborough’s depiction.

Moreover, consideration of the Sancho portrait as one of Gainsborough’s musical portraits helps to situate Sancho within London’s musical community. Like the Duke and Duchess of Montagu, Sancho became closely tied to the royal family of England, dedicating his 1776 Cotillions &c. to the Princess Royal, daughter of King George III and Queen Charlotte, when the princess was around 10 years old. He no doubt met members of the royal musical establishment, including Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel, both of whom were painted by Gainsborough, who was also their close friend. Gainsborough likewise painted a portrait of David Garrick, another of Sancho’s friends, whose theater management included oversight of musical productions as well as spoken theater.

Why, then, did Gainsborough not depict Sancho with a marker of his musicianship? The Gainsborough portrait depicts Sancho as a gentleman. His clothing, his posture, and his ironic facial expression all suggest a man of status and leisure. The absence of props like musical instruments asks the viewer to address the person alone, focusing not on what he did, but on who he was. This point does not erase his musicianship, but it places that musicianship in a secondary position to his personhood.

Gainsborough’s many portraits of musicians form a musical community unto themselves—a gallery of individuals bound by ties of artistry and friendship. Even without a musical instrument in hand, the Sancho of Gainsborough’s portrait should be considered part of that musical community. At the same time, it shows that Sancho’s musicianship was just one facet of his rich and complex life.