Teaching Ignatius Sancho in the Music Theory Classroom: Goals and a Sample Lesson Plan

Goals and a Sample Lesson Plan

By Martha Sullivan

This page is aimed at anyone who is interested in music and how it’s taught. This could include anyone from camp counselors to professors to parents to choir directors. Many readers will already be familiar with some of the ideas presented here. Nevertheless, I hope that everyone will find at least one item here that’s new to them and useful, as well as links to helpful resources online. I’ve divided this document into several sections:

-

- On Lesson Plans

- Music Lesson Plan Objectives and Activities in General

- Objectives Involving Sancho

- Sample Lesson Plans for Particular Topics

On lesson plans

Lesson plans can include many things. On a basic level, experts typically recommend that they include learning objectives, class activities that will move towards those objectives, and the methods teachers will use to assess whether students have learned what was intended. Universities usually have centers for teaching and learning that offer resources on lesson plans, and those are often accessible to the public. One such may be found here.

Experienced teachers will have their own systems in place; I offer these ideas to supplement what teachers have developed on their own. I also hope to offer the kind of resource I wish I’d had when I first started teaching!

Music Lesson Plan Objectives and Activities In General

Music teachers teach students of all ages and levels, in a wide variety of situations, cultivating in their students an extraordinary range of skills; music is complex. Therefore, many learning objectives and classroom activities are specific to a given discipline. Others, however, cross disciplines. I myself will probably never have to know how to make an oboe reed, or transcribe medieval motets into modern notation; however, in all the many areas I teach, some elements remain constant, whether I am teaching an 8-year-old to read music, a 15-year-old to compose it, a 19-year-old to understand its harmonic structures, a 40-year-old to sketch those harmonies on a piano, a 55-year-old to bring all the aspects of musical structure, dramatic purpose, text, and vocal technique together into a convincing audition performance, or a complete choir of individuals to bring everything they know about music together into a unified group performance (all of which I’ve done over a teaching career of a few decades). Here are some of the broadly applicable objectives I am for, and the activities I typically introduce to move towards them.

-

- OBJECTIVE: I always aim to create an embodied understanding of music. ACTIVITY: I will therefore always ask students to move to music, whether that means conducting, clapping, walking, tapping, or dancing.

- OBJECTIVE: I always aim to help students gain proficiency at hearing and performing music. ACTIVITY: I will therefore always ask them to “break it down to build it up” (thanks to Tovah Feldshuh for the particular phrasing).

- OBJECTIVE: I always aim to help students claim an individual voice. ACTIVITY: I will therefore always ask them to claim a voice by creating their own music, either in improvisation games or in assignments that ask them to compose music. This is especially important for students whose marginalized identities have made it difficult to find such opportunities, and safe spaces in which to explore musical creation.

Objectives Involving Sancho

The National Association for Music Education’s statement on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion describes a plan of action for meeting the needs of students of music, particularly those from groups that have been, or continue to be, marginalized. I recommend reading it closely. As I understand it, it suggests four main areas of action:

-

- first, curricula should engage a much broader range of repertoires and creators than they have in th epast (i.e., broader representation is needed in the materials studied);

- second, teachers should be trained in culturally responsive pedagogy (i.e., they should learn to teach a broader curriculum effectively to a more diverse cohort of students);

- third, teachers as a group should become more diverse (i.e., the education system needs to recruit and train a much more diverse pool of educators);

- fourth, the music classroom needs to meet the needs of ALL students.

Sancho’s music in the classroom helps greatly with the first and fourth goals, because to engage with his music is to provide representation, and representation of Black composers benefits all students, especially those who see in Ignatius Sancho an accomplished man who looks like them. The second goal—training teachers in culturally responsive pedagogy—is large and complex and beyond the scope of this essay, although some of the ideas herein may contribute to that goal; and the third goal—a diverse group of teachers overall—will be achieved over time, growing from the others, as those of us currently teaching music take care to nurture diversity in the rising cohorts of students we teach With this in mind, here are some learning objectives that can be achieved with Sancho’s help.

-

- Students should understand that composers have a diverse range of identities, so I will present works by Sancho and other composers whose identities are or were not privileged.

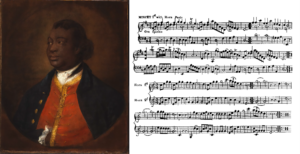

- The idea of Black musicians as composers should come to seem normal, so when using slide decks to present a composer like Sancho and his works, I will include the composer’s portrait prominently in the slide deck. Additionally, I will seek out performances by performers who represent diverse identities. Note: Other pages on this site feature several such performances.

- Students should understand that composers who share an identity do not all write the same kind of music (Ignatius Sancho’s music sounds different from Florence Price’s, which sounds different from Jessie Montgomery’s, which sounds different from Kendrick Lamar’s). Even within a single era, Black composers’ works will sound different from each other: Sancho’s music does not sound like that of Joseph Bologne, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, nor does Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s music sound like Florence Price’s, for example. The implementation of this goal will vary depending on the context—a class on the Classical period, for example, will not include work by more recent composers, so a comparison between, say, Sancho and Count Basie would never be presented. However, a class on music for social dancing in various eras might well juxtapose those two very different compositional voices.

- Particularly in diverse classrooms, all students should experience opportunities to express themselves, to claim their unique voices as creators. To achieve this goal, I will use exercises such as structured improvisation or composition to give everyone the experience of creating music. Sancho is an excellent model here, since he was a notable writer as well as a composer; his experience suggests that even when faced with substantial barriers to the creative process, it is both worthwhile and possible to find an outlet for what one wants to say. Teachers can and must facilitate this.

Sample Lesson Plans for Particular Topic

Please feel free to adapt these to your own classroom needs. Each contains more content than would normally fit into a single class; you can trim as desired, or use what’s presented over multiple class meetings. Or, simply adapt any general ideas that appeal to you to your existing lesson plans.

Music Theory and Performance: Binary Forms and Social Dance

Objectives:

-

- Students should understand connections between binary forms and social dance.

- Students should make the connection between regular phrase length and the structure of dances.

- Students should be able to feel the difference between duple and triple meter.

- Students should be able to recognize binary forms including simple binary, balanced binary, and rounded binary; they should also be able to state whether a binary-form piece is sectional or continuous.

- Students should reinforce concepts leading up to this class, including phrase structures such as periods and sentences.

Note: This lesson plan does not explicitly address racial issues. However, by using examples that highlight a Black composer and Black performers, the teacher can normalize the idea of Black agency and the agency of non-white makers of music overall without explicit discussion of the topic. This may be helpful for Black students, since it is an implicit affirmation of their presence in the classroom and the world of professional music making. This may also be a useful strategy in situations where explicit discussions of racial issues and structures of privilege are not welcome.

Before Class

For the teacher: Choose the videos you wish to present, from this section, from other sections of this web site, or from elsewhere on the internet. Collect the URLs on one document, or put them in a slide deck for use during class.

If you wish to use a shared document (as for example a Google Doc on Drive) for brainstorming or for an exit ticket at the end of class, set it up in advance and add the URL to your list of URLs or your slide deck.

For the students: Assign students to read about binary forms, and about their dance context, if you want to emphasize that. You will have a better idea than I will of how much material your students can handle for homework, and whether or not most of them will do it!

EQUITY TIP: When possible, assign readings from open access textbooks, available online at no cost, so that the price of textbooks is not a barrier to access. A clear text on binary form, usable from advanced high school classes through college and beyond, appears here (Robert Hutchinson, “Binary and Ternary Form,” Chapter 24 in Music Theory for the 21st-Century Classroom).

A more complex text appears in Brian Jarvis, “Binary Form” (in Open Music Theory, Version 2, published online by VIVA Open Publishing), with some nuanced ideas, but I do not recommend it as a starting place. I might assign it for a college class specializing in instrumental repertoire of the Classical era.

Both these books are useful, but they share the same issue: the examples in these chapters are all by white men. By contrast, Clendinning and Marvin’s The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis is an excellent text, and its authors have conscientiously curated a set of examples by diverse composers throughout. However, the online version costs, as of this writing, close to one hundred dollars, and print versions are more expensive. I do believe the book is worth its price, though. I might assign it in a theory class in which I knew all the students had a robust budget for textbooks, but in many of my classrooms, this is not the case. It may be worth discussing policies for fair use with one’s institution. Here is the publisher’s link to the Fourth Edition (current as of this writing).

Dance video: This is a Smithsonian video, rather short, introducing the basic steps of the minuet. One interesting connection: the house being documented is the one where the second Duke of Montagu, the one who encouraged the young Ignatius Sancho to learn to read, hosted balls. This video not only shows the dance, but also the elaborate manuscripts that showed particular choreographies.

You can also use the video on Ignatius Sancho’s minuets produced for this project.

During Class

Signpost: At the beginning of the class, let the class know what you will all be doing today, perhaps with an introduction like this:

— Today we want to understand (choose the right number of things for the level of class and for the amount of time you have; write them on the board, or make a document to print out and distribute):

-

- What is a minuet (in terms of the music and the dance)?

- What is the difference between duple and triple meter? (on paper and/or in your body)

- How long is a standard phrase of dance music in the Classical Era? Why do you think that is?

- What, in general, is a binary form? What does “reprise” mean when we are talking about binary forms?

On YouTube, listen to and watch performances of particular dances. I would start with ones that just show the performers, not the score. Choose videos for various criteria:

-

- Representation (use Raritan Players videos and dance videos made for the Sancho Project)

- Beauty (use Raritan Players videos and dance videos made for the Sancho Project)

- Regularity of pulse, for doing walking/dancing exercises

- Scrolling score, if you like to teach analysis using that type of video.

Explain/clarify the types of binary form you want them to master, asking students to share what they think binary forms are on the basis of the reading they hopefully did before class. Ideally, this would involve looking at scores carefully; if possible, make slides of the scores with a portrait of Sancho as part of the design. A sample slide might look like this (Figure 1):

You can ask specific questions about an excerpt to generate discussion, then generalize from there, or the reverse. Questions about this particular minuet might include the following, depending on what else you have discussed in class:

-

- What key or keys is this piece in?

- What is the meter?

- How does the meter relate to the title of the piece?

- How long are the phrases? Why do you think that’s so?

- Where are the cadences? How did you find them? Which ones cadence on I, which on V?

- Motivic analysis: what do you see and how does Sancho use it—where do you see melodic material repeat?

- Formal details: sectional or continuous binary? Balanced binary (first part and second part use the same cadential material, either transposed or in the key of the piece)? Rounded binary (return to tonic marked by a return of opening material from the first half)

For composers, conductors, and future orchestral professionals in general:

-

- Why do the horns seem to be in C?

- Can you turn this thin notation into a full score?

- Difficulty: Does Sancho give anyone a line that is much easier than other players’? If so, why might he have done that?

General questions and reflections, based on reading homework and analysis in class, might include:

-

- What is the difference between sectional and continuous binary form?

- What is a balanced binary form?

- What is a rounded binary form?

- What is a simple binary form?

Reinforce earlier material:

-

- What is the difference between duple and triple meter? Is this dance in 2 or 3? How do we know? What do the two types of meters feel like? Let’s try them to find out! (Assuming you have enough space in the classroom to walk; if not, you may solicit volunteers to walk at the front of the class, or have people walk in place next to their desks.)

- What is a parallel period?

- What is a sentence?

- What is a melodic sequence, and what is a harmonic one?

End of Class: Watch another dance video, or re-watch one from the beginning of class, asking students to notice any differences in their perception now that they have talked about structure and applied it to actual performances. If desired, ask students to write down a quick thought about how their perception changed (on an index card or on a document you share in Google Drive or via a similar sharing platform) as an exit ticket.