Sancho’s Wise Fool: Making Sense of “Mungo’s Delight”

By Rebecca Cypess

rcypess@mgsa.rutgers.edu

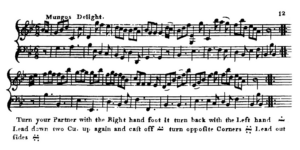

A year before his death, Ignatius Sancho published his Twelve Country Dances for the Year 1779, which closes with a piece titled “Mungo’s Delight” (Figure 1).

Ignatius Sancho, "Mungo's Delight," from Twelve Country Dances for the Year 1779. Rebecca Cypess, Square Piano.

While the name “Mungo” was known to some in connection with St. Mungo, the patron saint of Glasgow, Scotland, Sancho’s use of the name is more likely a reference to the blackface character Mungo from The Padlock, a comic opera premiered in 1768 with text by Isaac Bickerstaff and music by Charles Dibdin.

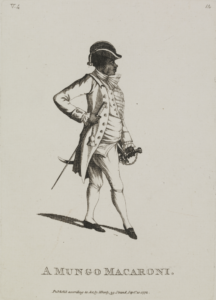

While blackface characters had appeared on the British stage before, Bickerstaff’s and Dibdin’s Mungo was especially problematic: Mungo, originally played by Dibdin himself, speaks in a laughable dialect and behaves in a disturbingly comical way. The Padlock became wildly popular, achieving record success in London and provincial British theaters and reaching audiences across the British Empire from Kingston to Calcutta. The damage that it did through its laughable portrayal of Mungo is inestimable. So widely known did the figure of Mungo become that, by the time Sancho’s Twelve Country Dances appeared in print, the name Mungo had come to be used to refer disdainfully to all Black men. Sancho’s friend and correspondent Julius Soubise was caricatured as a “Mungo Macaroni” (Figure 8.2) when he reportedly adopted affectations and a mode of dress that were considered flamboyant and inconsistent with his perceived station.

Julius Soubise was caricatured as a “Mungo Macaroni” (Figure 2) when he reportedly adopted affectations and a mode of dress that were considered flamboyant and inconsistent with his perceived station.

At the same time, paradoxically, some Black people in London began referring to themselves as “Mungo.” Such usage occurred, for example, after the 1772 legal decision known as the Somerset case, which made it illegal for an enslaved Black person in Britain to be forcibly removed to Jamaica and put up for sale. Such instances suggest that Black Londoners had begun to adopt the character of Mungo, reappropriating and reinterpreting it as a vehicle of resistance.

This idea opens the way to an understanding of Sancho’s dance piece “Mungo’s Delight.” Why would Sancho have used a name that demeaned Black people? I think that Sancho, like other Black men of his day, reappropriated and reinterpreted the name. Specifically, I think it represents one of many instances in which Sancho adopted the persona of the “wise fool.”

The wise fool was a character with whom Sancho’s readers and audiences would have been well acquainted. The basis of this figure in Christian theology and morality is made clear in 1 Corinthians: “But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world, to confound the wise; and God hath chosen the weak things of the world, to confound the things which are mighty; And base things of the world, and things which are despised, hath God chosen.”

Sancho’s friend and correspondent Laurence Sterne used the trope of the wise fool throughout his writings. At the very opening of Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy, the title character addresses the reader and admits that his book is a little odd, but he instructs the reader to “have a little patience” while they get to know one another:

Therefore, my dear friend and companion, if you should think me somewhat sparing of my narrative on my first setting out,—bear with me,—and let me go on, and tell my story my own way:—or if I should seem now and then to trifle upon the road,—or should sometimes put on a fool’s cap with a bell to it, for a moment or two as we pass along,—don’t fly off,—but rather courteously give me credit for a little more wisdom than appears upon my outside;—and as we jogg on, either laugh with me, or at me, or in short, do any thing,—only keep your temper.

Like a jester wearing his fool’s cap with a bell to it Tristram Shandy would go on to present prophetic truths. Among these is the story of a young Black girl in a shop who shooed away a fly with a feather, rather than killing it. The reaction of the main characters to this touching scene shows the extent of their naïve wisdom: ’Tis a pretty picture! said my uncle Toby—she had suffered persecution, Trim, and had learned mercy—. Toby goes on to affirm the basic, common humanity of all people, regardless of their outward appearance. This was the story to which Sterne referred when he responded to Sancho’s letter asking that Tristram Shandy address the question of slavery:

There is a strange coincidence, Sancho, in the little events (as well as in the great ones) of this world: for I had been writing a tender tale of the sorrows of a friendless poor negro-girl, and my eyes had scarse [sic] done smarting with it when your Letter of recommendation in behalf of so many of her brethren and sisters, came to me—but why her brethren?—or your’s, Sancho! Any more than mine?

Sancho, a Black man in predominantly white London and someone who needed to retain relationships with his powerful white patrons and friends, had good reason to frame his critiques of prejudice, discrimination, and slavery subtly. By assuming the character of the wise fool, he found an indirect route to register his protest.

Wise fools with whom Sancho identified appear throughout his letters. One example is an impassioned letter to his friend John Meheux that opens with the heading “Jack-asses.” Here, Sancho seethes about the mistreatment of donkeys by a band of thieves that plagued his shop on Charles Street:

A tall lazy villain was bestriding his poor beast (although loaded with two panniers of potatoes at the same time) and another of his companions, was good-naturedly employed in whipping the poor sinking animal—that the gentleman-rider might enjoy the twofold pleasure of blasphemy and cruelty—this is a too common evil—and, for the honor of rationality, calls loudly for redress.

Sancho claimed a special affinity for the jackass, writing: “I ever had a kind of sympathetic (call it what you please) for that animal—and do I not love you?” Here Sancho may have been referring to Tristram Shandy’s claim that “my mule loved society as much as myself.”Sancho continued: “Before Sterne had wrote them into respect, I had a friendship for them—and many a civil greeting have I given them at casual meetings.”

The theological implications of Sancho’s “friendship” with the jackass emerge from the elevation of this lowly animal by Jesus, as Sancho notes: “what has ever (with me) stamped a kind of uncommon value and divinity upon the long ear’d kind of the species, is, that our Blessed Saviour, in his day of worldly triumph, chose to use that in preference to the rest of his own blessed creation—‘meek and lowly, riding upon an ass.’” Here Sancho describes the inversion of the social hierarchy that is central to Christianity, whereby the lowly beings who are abused and whipped by their would-be masters become exalted.

The implications of Sancho’s identification with the jackass are clear: Like the lowly jackass, whose social position will ultimately ascend to the lofty heights that his spirit already occupies, Sancho implied that he and other Black people, abused as they were in British society, would ultimately ascend to a similarly high station; those who dare abuse the lowly will receive their punishment at the hands of God.

The title of Sancho’s composition “Mungo’s Delight” has similar implications. While The Padlock used the name “Mungo” to demean and mock Black people, Sancho—like other Blacks in London and beyond—claimed the name for themselves.

While “Mungo’s Delight” is not a virtuosic piece, it does require some technical agility. The primary musical idea is its extensive leaps up and down the instrument. It is common for country dances to incorporate leaping motion in the melody. Yet Sancho adds to this by writing leaps of much larger intervals; these require precision and care on the part of the instrumentalist. It thus seems that Sancho uses the convention of leaping in country dances and builds upon it to enact and display musical and technical agility.

In writing Mungo’s music in this way, Sancho was reinterpreting the character, bringing him out of the world of comic fiction and inscribing him through the notated score in the musical soundscape of eighteenth-century London. Nor was the impact of this authorial act limited to London’s soundscape on a general level; rather, it animated the bodily movements of both Black and white dancers. “Mungo’s Delight” would almost certainly have been used to accompany social dancing in the circle of the Montagu family, and its publication meant that it was probably used among other families of the same social class as well as, perhaps, in public balls. Sancho’s dance music might also have been used in the Black-only dances known to have taken place in London. Thus ‘Mungo’s Delight’—and Sancho’s other instrumental dance compositions—animated the dancing bodies of a diverse society. Moreover, through his authorship in popular genres like the cotillion and the country dance, Sancho raised the possibility of other music in those genres being used by Black musicians and dancers as well. Sancho’s compositions thus expanded these genres as a dialectic space open to Black and white musicians, dancers, readers, and listeners.

Sancho’s use of the name “Mungo” in the title of one of his compositions should be understood as an act of affiliation; in this affiliation lay a sense of defiance. In making space for Mungo in his published volume, Sancho accepted him into a world—real or imagined—where his musicianship had a place.

***

To read more about Sancho’s use of the figure of the wise fool in both his music and his letters, see Rebecca Cypess, “The Poetics of the Wise Fool in the Music and Letters of Ignatius Sancho,” an article in the journal Music & Letters.