Ignatius Sancho and the Minuet

By Caroline Copeland

Adjunct Assistant Professor of Drama and Dance, Hofstra University

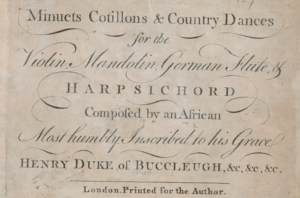

This danced enactment of Ignatius Sancho’s “Minuet #1” relies on French and English printed sources describing the dance form. The choreographer, Caroline Copeland, hopes to illuminate what the records show; the African diaspora, enslaved and free, played, composed, and performed dances popular across the British Empire.

August 27th, 1777

To Mr. R––

…and pray how does the aforesaid lady do?—Does she ride, walk, and dance, with moderation?

I. Sancho (Letter XLIX)

French in origin, the minuet spread with European colonial expansion to the ballrooms, assembly rooms, and theaters of the Caribbean islands and the Americas during the era of Ignatius Sancho. One of the most popular ballroom dances, the minuet is featured in every European dancing manual of the eighteenth century, and dance instructors advertised the teaching of the minuet, along with other popular ballroom dances, from London to Haiti to New York, in local newspapers.

Depending on the occasion, the minuet could be performed in couples, one after the other, or with several couples dancing simultaneously. The second practice is described by the Italian dance instructor, Gennaro Magri in his book Theoretical and Practical Treatise on Dancing (Naples 1779). Based on Magri’s description this seems appropriate for the livelier public balls and festivals, like those held at the Vauxhall Gardens, and where the space is large enough to accommodate several couples dancing at once.

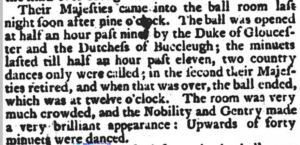

The newspaper account in Figure 2 describes a formal court ball where “upwards of forty minuets” were danced, one after the other. This extensive round of minuets appears to have taken two hours and was followed by only two country dances – not a very exciting night for those spectators who may have hoped to join in on the communal fun of country dancing.

For a formal ball held at court, such as the one described above, ladies who wanted to dance a minuet would have sent their names and ranks to the event’s organizers ahead of time. Preparatory dance lessons and formal court attire would be requirements as this kind of performance was not to be taken lightly; one false step could lead to great public embarrassment.

It is interesting to note that Sancho’s patrons were in attendance at this ball, and that Henry Duke of Buccleugh’s wife, Elizabeth, Duchess of Buccleuch, had the honor of leading out the first minuet of event in front of Their Majesties, George III and his wife, Charlotte.

As for Sancho, we do not know if he danced himself, but he certainly witnessed many a minuet when he served as a butler in the Montagu household. In his days as an aspiring young actor, dancing lessons may have been part of his training, but after gout side-lined him physically, his dancing days would have been behind him too. Sancho’s genteel graces, however, are on display in each of his letters, where his writing exhibits the very definition of a gentleman. And his children probably danced to their father’s music for personal enjoyment.

The Minuet: A Dance of Social Necessity?

The Minuet needs hidden control.…in order to make a good presentation. It needs a languid eye, a smiling mouth, splendid body, unaffected hands, ambitious feet

From Gennaro Magri, Theoretical and Practical Treatise on Dancing (Naples, 1779).

Since the Italian Renaissance, dance instructors were selling the idea of teaching morals, manners, and etiquette through dancing. Their teaching focused on bodily containment—a literal measuring of one’s physical actions in time and space. This concept of embodied manners carries through in all the European ballroom dances, especially the eighteenth-century minuet, where courtly etiquette is built into the structure of the dance.

Like Sancho, Lord Chesterfield was also a man of many letters. In his correspondence to his sons, he often refers to the minuet as the dance to learn, if for no other reason than to learn how to conduct oneself in public. For Chesterfield, it is a dance not of impertinence or insolence, but one requiring measured gestures, timing, and poise:

London, September 27, 1748

Dear Boy,

…Remember, that the graceful motion of the arms, the giving your hand, and the putting on and pulling off your hat genteelly, are the material parts of a gentleman’s dancing…all of which are of real importance to a man of fashion.

Lord Chesterfield

Varieties of Danced Minuets

In the eighteenth century, the minuet was practiced in different forms:

-

- In duet form, for a man and woman (see the video above),

- As a country dance performed in lines of men and women set across from each other,

- As a group form, for young women to display their “genteel graces” (see Pemberton’s “An essay for the further improvement of dancing” of 1711 in the bibliography below),

- And in a theatrical form, which uses more complex stepping and patterns.

Elements of the Dance

In the ballroom, the minuet for a couple could be considered a structured improvisation.

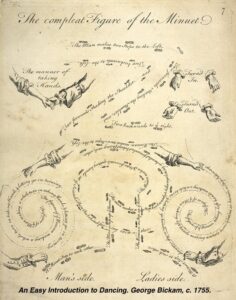

There was an order to the dance and basic figures to be performed: Opening Bows, Reversed “S” or “Z” Figures, Offering of Right and Left Arms, A Repetition of Reversed “S” or “Z” Figures, The Offering of Both Arms, and Final Bows.

But, interestingly, the minuet was not rigid in its structure; the form could expand and contract at the will of the performers and steps could be embellished, simplified, or even improvised.

However, there were a few caveats offered in the 18th century dancing manuals:

-

- First, don’t bore the spectators with too many “Z” patterns; there might be upwards of twenty minuets performed at a formal ball, so be considerate of your audience.

- Second, do not outshine your partner with too many fancy and filigreed steps or roll your eyes if they make a “faux pas,” or false step; that is impolite.

- Third, do not take on steps and airs you cannot embody confidently; always dance to your strengths.

Stepping Varieties

Dancing manuals printed in France, England, Spain, Italy, and Germany in the eighteenth century present a pleasing variety of approaches to rhythm and step possibilities. There was a basic minuet step (four shifts of weight in six beats) that could travel forward, backward, and sideways, but there was no single, “correct” way to execute it.

This basic step could be performed on the balls of the feet or flat-footed, and one could also add different kinds of springing steps and setting steps to the basic step for a more pleasing variety. What did not vary were the expected graces and graciousness of the participants.

The basic step of Sancho’s era is notated in Figure 3 by the French dance instructor, M. Malpied, ca. 1770. Figure 4 is a shorthand of the dance from George Bickam’s An Easy Introduction to Dancing from 1738.

Notes on the Video

The minuet presented in the video above is based on instructions from two primary sources, M. Malpied’s Traité sur l’art de la danse (Paris, ca. 1770) and Nicholas Dukes, A Concise & Easy Method Of Learning The Figuring Part Of Country Dances (London, 1752).

M. Malpied offers the reader some basic steps and rhythms to carry them through the dance, as well as notated bows and a fully notated minuet for a man and a woman. However, in creating the dance in the video at the top of this page, I found the “Z” patterns too repetitive. Malpied suggests four repetitions of the “Z” figure each time, but I chose to shorten that to two patterns (rule #2: Don’t bore the viewer!).

Mr. Dukes’s instructions offer no steps but suggest that the length of each figure is not necessarily set, so some patterns could take six measures (“Z” Patterns), another seven measures (Right Arm Figure) and still another five measures (Left Arm Figure). I tried to follow his suggested route.

Finally, I chose no “fancy” steps for this minuet and opted for the basic step only. Based on Sancho’s letters, one gets the sense he was against affectation, or the putting on of airs; elegant simplicity was our aim.

Embodied Dance Historian Tip: Always go to the Source!

For Further Reading of Original Sources on the Minuet

A Comprehensive List of Original Sources: Library of Dance

E. Pemberton’s, “An essay for the further improvement of dancing, 1711.

Malpied, Traité sur l’Art de la Danse. Paris. ca. 1770.

For Further Information on Images of Enslaved Africans

Newspaper Accounts and Advertisements

The Performing Arts in Colonial American Newspapers, 1690-1783

The Digital Library of the Caribbean