Transatlantic Dance Traditions: A Comparison of Tobago Jig and English Country Dancing from the Era of Ignatius Sancho and Beyond

By Caroline Copeland and Kieron Sargeant

Video Description: This video compares two dance traditions forged and transformed under the British Empire and beyond, Tobago jig and English country dancing. The choreographers, Caroline Copeland and Kieron Sargeant, hope to illuminate what the records show; the African diaspora, enslaved and free, played, composed, and performed dances popular across the British Empire and then transformed those dances into new and vibrant traditions still practiced today.

____________________

The dances and music of the Afro-British composer Ignatius Sancho sparked many inquiries into 18th century dance practices. Specifically, questions arose of how, and if, free and enslaved Africans living in London during Sancho’s era would have danced to his music. Sancho composed music and dance music in the English, French, and Scottish styles; did his family dance in these same styles? Did the free and enslaved Africans living in London dance to his collections of music, and, if so, how?

We will never know precisely the distinctive genius their collective experiences would have infused into these dance forms. Furthermore, it remains uncertain whether free and enslaved Africans in London danced to Sancho’s compositions at the all-Black balls mentioned in newspapers. An example of such an event was reported in the Massachusetts Spy in Boston on August 5th, 1773:

[London] Among the sundry fashionable routs or clubs that are held in town, that of the black or Negro servants is not the least: On Thursday night no less than 59 of them, men and women, supped, drank, and entertained themselves with dancing and music; consisting of violins, French-horns, and other instruments, at a public-house in Southwark. No whites were allowed to be present, for all the performers were blacks.

Massachusetts Spy, Boston

The Tobago Jig

A fruitful starting point for this research is the Caribbean, where diverse European dance traditions were initially adapted by enslaved Africans and subsequently transformed and preserved by successive generations. A notable example is the Tobago jig, a dance that seamlessly blends Africanist and European dance and music forms into a vibrant mode of expression.

Initially performed to mark rural weddings, christenings, and other festive occasions, the Tobago jig was crafted by enslaved Africans for the purposes of ritual, pleasure, and satire. By mimicking the movements of British enslavers (as depicted in the satirical print in Figure 1), this comedy of manners has evolved over the past three centuries into a cherished dance emblematic of Tobago’s heritage and culture.

Living Traditions Transformed

The Tobago jig is a lived tradition that has been preserved and passed down from generation to generation by elders who teach in their local communities and schools. Each town in Tobago has its unique style of dancing the jig, and the dance can be adapted for different numbers of couples and different occasions.

English country dancing is also a lived tradition that spread to the British colonies where the form was adapted locally into various styles and forms. The height of its popularity was the late 18th century and early 19th century, when its zenith was eclipsed by different crazes of couples’ dances, like the waltz and polka of the 19th century. This dance tradition, transformed by time and multicultural influences, was still alive in rural areas of England, the Caribbean, and the Americas in the early 20th century, when a renewed interest in these forms took hold in England and the United States.

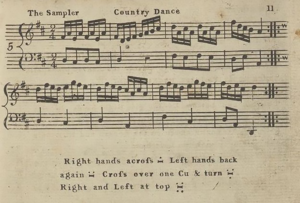

To uncover how the dances could have looked and sounded during the era of Ignatius Sancho and what stepping would have been done, an embodied dance historian can consult dancing manuals of previous centuries in order to re-imagine them. (See the video at the top of this page.) The country dance collections published by Sancho are one such resource (see below). Sancho’s collections give the reader figures, or instructions for the dance, along with his musical composition, so the dancer knows where to go in space but not always what the steps were.

Harmonies of Heritage: The Africanist Transformation of the Tobago Jig

The foundational structure of the Tobago jig bears resemblance to the country dances and cotillions of 17th- and 18th-century France and England, and the stepping and costuming are influenced by 18th- and 19th-century English and Scottish country dances, reels, and European polkas. However, it is the Africanist influences, particularly from Igbo, Kongo, Ibibio, Yoruba, and Malinke people, that transformed these European ballroom dances and music into the lively, full-embodied expression of the modern Tobago jig.

The Ritual Aspect

Originating from Pembroke, Tobago, the Tobago jig is an indigenous dance form that carries pronounced African influences from West Africa. Unlike the secular nature of English country dancing, the Tobago jig was traditionally a ritual dance performed to summon the presence of ancestors and the departed, often accompanied by tambrin music. The tambrin drum was created by slaves after the British colonial government outlawed traditional African drumming, music, dances and religious worship. This percussion instrument is often used during ceremonial occasions and usually accompanies one of the island’s distinct dances, the Reel and Jig. The jig also possesses a subversive function, subtly mocking colonial masters while discreetly housing African spiritual practices in plain sight.

The Tobago jig eventually found its place in various ceremonies and festivals, such as the Tobago Heritage Festival, Mt. Moriah Old Time Wedding, wakes for the deceased, boat launchings, moments of sickness and recovery, and the pre-wedding Bachelor’s night. Prior to engaging in the dance, a customary practice involves pouring a libation of white rum and water in the road, symbolizing an invitation to the ancestors to join the celebration in the yard.

The Movement and the Music

The dynamic shifts in posture and use of the torso enliven the already lively and game-like structure of a country dance or cotillion. The Africanist movements, more grounded and rooted, are played in contrast to the uprightness of Europeanist ballroom dances. The musical accompaniment evolved from a Europeanist folk tradition (using violin, flute, harpsichord) to the polyrhythmic tambrin band (using differently pitched drums, triangle, sometimes violin, and voice). The tambrin band normally includes five musicians playing three frame drums, or tambrins, one triangle, and one violin and/or, more recently, a harmonica. The drums are called the cutter, roller, and bass or boom. These drums are tuned to different pitches through a process whereby the frame drums are heated by holding them over an open fire.

Breaking It Down: Similarities/Differences to Note in the Video

- The Skirts

The colorful expression of the womens’ skirt manipulations (Figure 4) is an essential part of the Tobago jig. The swirl of colorful fabrics is a vibrant extension of the dancers’ movements, and this feature has only been enhanced with the dance’s transformation from a ritual and social dance to a stylized folk dance at the Tobago heritage festivals.

In contrast, in the European ballroom tradition, women were counseled to hold their skirts delicately between the thumb and forefinger. This convention was more out of necessity than anything else, as it ensured that the lady would not step on the hem of her dress. But this small detail also required artful consideration of the woman, who was always supposed to maintain an air of modesty on the dance floor (Figure 5).

- The Footwork

A variety of stepping was utilized in Sancho’s era of country dancing and in today’s Tobago jig. Both dance forms allow room for improvisation, adaption, and caprice, and both forms empower the dancer to express the dance to the best of their ability.

For the dances that Sancho composed, 18th-century English, Scottish, French, and German steps were possible. In this video, choices were made by the choreographer and the participants, but all decisions were based on extant dancing manuals of the 18th and early 19th centuries (see below for bibliography).

See the video for comparisons of certain steps and figures across both dance forms.

Embodied Dance Historian Tip: Always go to the source!

____________________

Further Reading of Original Sources:

18th Century Country Dancing Sources

A Comprehensive List of Original Sources: Library of Dance

Tobago Jig Sources/ Caribbean Dance Sources

Daniel, Yvonne. Caribbean and Atlantic Diaspora Dance : Igniting Citizenship. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Manual, Peter, Editor. Creolizing Contredance in the Caribbean. Temple University Press. 2009

Andreas Meyer. Moving Across a Stylistic Continuum:Tambrin Music in Tobago. 2011.

Miller Monica L. Slaves to Fashion : Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. Duke University Press 2010.

Presto, Thomas Talawa – (PhD Candidate and Artistic Director of Tabanka Dance Ensemble)

Sloat, Susanna, and Susanna Sloat. Caribbean Dance from Abakuá to Zouk : How Movement Shapes Identity. University Press of Florida, 2002.

Tobago’s arts & culture: An overview hptt://www.discovertnt.com/articles/Tobago/Tobago-Arts-Culture-an-Overview/70/4/16#axzz8OiSWAv2Z

For Further Information on Images of Enslaved Africans: