Ignatius Sancho and Country Dancing

By Caroline Copeland

Adjunct Assistant Professor of Drama and Dance, Hofstra University

This enactment of three of Sancho’s country dances relies on English, Scottish, and French printed sources describing the dance form. The choreographer, Caroline Copeland, hopes to illuminate what the records show; the African diaspora, enslaved and free, played, composed, and performed dances popular across the British Empire.

In Ignatius Sancho’s era, dancing and music making were popular forms of both public and private entertainment. There were public balls held in local assembly rooms, private balls in the palaces and homes, and outdoor frolics of free and enslaved folk, respectively. There were also celebratory balls, like the all-Black ball held in London in 1772 to celebrate the victorious court case affirming that the formerly enslaved James Somerset could not be forcibly removed from English soil and returned to slavery.

[London] June 25, 1772

On Monday near 200 blacks, with their ladies, had an entertainment at a publick house in Westminster, to celebrate the triumph which their brother Somerset had obtained over Mr. Stewart his master. Lord Mansfield’s health was echoed round the room, and the evening was concluded with a ball. The tickets for admittance to this black assembly were five shillings each.

The New York Journal

Communal enjoyment of music and dance was not just a public affair but a familial one, too. The following letter from Ignatius Sancho to Mrs. Francis Crewe attests to the practice of creating figures to dance as a sociable exercise. Here, Sancho wrote a tune and passed it on to Mrs. Crewe, suggesting her son fill in the dance music with his own figures. This begs the question of whether Sancho’s own wife and children engaged in the same pastime.

November 5, 1777

To Mrs C––

… But to conclude—the little dance (which I like because I made it)– humbly beg you will make Jack play—and amongst you contrive a figure.

I. Sancho (Letter LV)

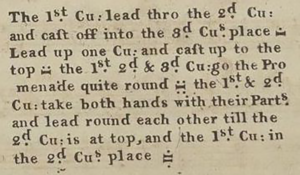

Most of the music Sancho composed and published was dance music, including menuets, cotillions, country dances, reels, and a hornpipe. Sancho printed the figures (spatial patterns) along with his music, but he only mentions a few steps or step patterns; this was typical practice in his day. A country dance is like a cross-stitch sampler in action. The figures, or the pathways of the dance, carry the dancers through the space in kinetically embroidered patterns, some linear, some circular. Steps of the dance could range from complex jumping and skipping actions to simple walking.

Figure 1 shows an example of Sancho’s description of figures for his country dance “The Runaway.”

How did folks know which steps to do?

Knowledge of the dances and their steps came from different sources: personal observation, public or private lessons, and/or the reading of instructions offered in papers, pamphlets, and books.

Written Sources

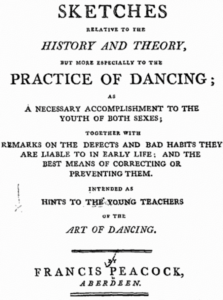

During Sancho’s era, numerous dance treatises and newspaper articles describing the popular dance steps were published. Those same sources were consulted in the making of these videos. For example, Nicholas Dukes’s Concise and Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances (1752, Figure 2) offers samples of the patterns in space; Francis Peacock’s Sketches Relative to the History and Theory, but More Especially to the Practice of Dancing (1805, Figure 3) offers Scottish stepping appropriate for reels and some country dances.

Instruction in the Home

Dance and music instruction were also conducted privately in the homes of wealthy families where siblings, with cousins, and friends would come together to practice their steps for the next season of balls. This practice is attested to in the letters of Martha Washington to Abigail Adams:

Tuesday morning January 25, 1791

Mrs Washington, presents her compliments to Mrs Adams,— if it is agreable to her, to Let miss smith come to dance with nelly & Washington, the master attends mondays wednesdays and Frydays at five oclock in the evenings— Mrs Washington will be very happy to see miss smith…

Martha Washington

Public Classes

Public classes were advertised by dance instructors in local papers and held in local assembly rooms. Below is one such advertisement by Henry Holt, a British dance instructor working in Manhattan. Holt was also the enslaver of a Black fiddle player named Joe, who most likely accompanied Holt’s dance classes as well as playing for public balls.

July 4, 1737

Ball, in New York, public, sponsored by Henry Holt, dancing master

On Thursday July the 14th, at the house of Mr. De Lancey, next door to Mr. Todd, will be a ball. Henry Holt, Master. The said Henry Holt hopes he is sufficiently qualified to teach, having serv’d his time to Mr. Essex, jun. one of the most celebrated masters in England, and danc’d a considerable time at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane. NB. The days appointed for teaching are Mondays and Thursdays, in the afternoon….

The New York Weekly Journal

Personal Observation

Like most enslaved house servants of the Americas and the Caribbean islands, Sancho, was witness and perhaps participant in the music making and dancing in the home.

Accounts of enslaved servants dancing range from descriptions of formal balls to livelier frolics in taverns and fields, but these are only told through the eyes of colonizers (see Figure 4). As a dance historian who relies on embodied practice as a method of research, I wish these writers spent less time opining and more time describing the actual dances. What did the enslaved participants dance?

One guesses that on more formal occasions the dancing took on more European forms from the elite households in which they worked. But the frolics held at taverns and on the outskirts of towns likely reflected the participants’ various African heritages together with French, English, and Scottish steps and music, thus giving birth to new American and Caribbean dance forms. For example, see the video that we have created for this project comparing the Tobago jig with English country dancing and the video comparing the Trinidadian bélé with the minuet.

The following is a description of a frolic in a tavern from eighteenth-century Boston:

January 14, 1740

Last Friday night a gentleman of this town went over to Roxbury to look for his Negro woman, who had been gone from him a few days; and hearing a noise in the tavern, he went in, (past nine o’clock) and found about a dozen black gentry, he’s and she’s, in a room, in very merry humour, singing and dancing, having a violin, and store of wine and punch before them….

Boston Evening Post

Compare that description with the following portrayal of a formal ball in Jamaica:

The mulattoes likewise at this season have their public balls, and vie with each other in the splendour of their appearance; and it will hardly be credited how very expensive their dress and ornaments are, and what pains they take to disfigure themselves with powder and with other unbecoming imitations of the European dress. Their common apparel at other times, and mode of attiring, are picturesque and elegant; and as the forms of the young women are turned with equal grace and symmetry, and as their motions in the dance are well calculated to show off their make to the greatest advantage….

From William Beckford, A Descriptive Account of the Island of Jamaica (1790)

Did everyone dance the same way?

Dance instructors of the eighteenth century promoted teaching to the individual student, their unique temperament, age, and ability. One assumes there was a more staid style at formal occasions and more lively improvisations at frolics, taverns, and private parties.

We will never know exactly how the dancing looked, but eyewitness accounts of balls and parties allude to a certain amount of individuality mixed in with practiced conventions. Everyone made their way through the dance the best they could.

February 28, 1786

There were 27 Ladies present, and about 20 Gentlemen. There were a number of strangers among the Gentlemen; I might make a number of sarcastic reflections, upon the manner of dancing, and appearance of several persons there; but I do not think it is a matter of sufficient importance to induce one, to laugh, at a person who cannot show the elegance of a dancing master; and if it is; as I did not dance myself, it would be unfair to laugh at those, who had they had the opportunity might have laugh’d equally at me. It is base to ridicule a person for any failing that is owing to no mental vice or foible.

There was one Lady present (Mrs. Payson) for whom I was anxious all the Evening: I feared she would; while she was throwing herself about, be taken with a different kind of throes. It is exceedingly imprudent for a Lady in that Situation to frequent such places…

John Quincy Adams

Notes on the video from the choreographer

In our video for this project, the dancers adapted the steps I suggested based on their experience and dance training. Sometimes, the dancers chose to simplify the steps and sometimes they added extra shifts of weight. I believe this individual approach to stepping is in keeping with 18th century practice and enlivens the performance and the practice of the form.

Embodied Dance Historian Tip: Always go to the source!

Original Dance Sources

A Comprehensive List of Original Sources: Library of Dance

Sr. de La Cuisse, Le Répertoire des Bals, ou Theorie-Pratique des Contredanses. Paris, 1762.

Simon Guillaume, Almanach Dansant; Ou Positions & Attitudes De L’Allemande. Paris, 1769.

Information on Images of Enslaved Africans

Newspaper Accounts and Advertisements

The Performing Arts in Colonial American Newspapers, 1690-1783

The Digital Library of the Caribbean