Transatlantic Dance Traditions: A Comparison of Trinidadian Grand Bélé and French Minuet for Two

By Caroline Copeland and Kieron Sargeant

This video compares two dance traditions forged and transformed under the British Empire and beyond, the Trinidadian Grand Bélé and the French Minuet. The choreographers, Caroline Copeland and Kieron Sargeant, hope to illuminate what the records show; the African diaspora, enslaved and free, played, composed, and performed dances popular across the British Empire and then transformed those dances into new and vibrant traditions still practiced today.

_________________________

This essay and the accompanying video above explore a comparison between Trinidadian grand bélé and the 18th-century European minuet for a man and a woman. The inspiration for this idea stems from an examination of two primary sources: the music and dances of Ignatius Sancho and advertisements of all-Black balls in London, dating from the later half of the eighteenth century.

Ignatius Sancho’s published dance music was written in the French, English, and Scottish styles, consisting of menuets, cotillions, reels, and country dances. However, the question arises; how did members of the African diaspora living in London dance these forms at their exclusive gatherings? While we may never know, contemporary dance traditions in the Caribbean, created by enslaved Africans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, embody a fusion of Africanist and European forms and rhythms; one such dance is the bélé.

Historical Context of the French Minuet and Trinidadian Grand Bélé

The minuet is French in origin but its popularity spread to all of Europe in the early 18th- century. It then traveled beyond with European colonial expansion to the French and British colonies where the minuet was imitated and transformed by enslaved Africans into what is now known as the bélé. Today, the living tradition of bélé dance and music can be witnessed in various Caribbean locations, including Martinique, St. Lucia, Dominica, Haiti, Grenada, Guadeloupe, and Trinidad and Tobago.

The minuet for a man and a woman was the embodiment of European courtly etiquette in the eighteenth century– a presentation of idealized physicality that was promoted and prized by 18th-century dance instructors as the dance for young ladies and gentlemen to learn. At formal balls, the first dances presented were minuets whereby each couple took turns performing for their peers. Upwards of forty minuets in a row could be performed at the most formal events lasting an hour to two hours. After which a series of quadrilles, cotillions, and country dances would end the evening.

The engraving in Figure 1 depicts a couple performing one of the minuet’s typical figures, or patterns in space, the “Z” or reversed “S” figure. In this particular pathway, the man and woman trace the figure of a “Z” without touching or holding hands. This kind of serpentine pathway, ornate and indirect, was considered a “line of beauty” in baroque art and dancing.

In the late 18th-century French enslavers and plantation owners, fleeing the revolution in Haiti, relocated to Trinidad and Tobago. They brought with them their music and dances, including the minuet which their enslaved servants observed at formal balls.

Figure 2 is a satirical print depicting “A grand Jamaica ball!” A crowd of Black spectators observe their enslavers in various throes of flirtation, drinking, and lively dancing; the vicar and the lady in white look particularly virtuosic and comical. Above them, in the musicians gallery, are a band of enslaved instrumentalists on the left, all playing the violin. On the opposite end of the gallery are white musicians playing winds, horns, and percussion.

Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Wealthy households in the Caribbeans and Americas often employed bands of enslaved musicians. Ads for runaway slaves attest to this practice. Even dance instructors used enslaved violinists for their lessons and balls as discussed in the article on the minuet on this website).

Quickly adapting the music, fashion, and movements of the enslavers, new music and dance forms emerged in the rural frolics and fetes of enslaved servants and field hands.

One new dance, the bélé, featured grand entrances, ceremonial bows, and sweeping, gentle movements, imitating the elegance of the French minuet. Over time, this dance evolved and today, different genres and traditions of this dance can be found wherever the French settled in the Caribbean.

The grand bélé of Trinidad is one genre of bélé that has some hallmark similarities to the earlier minuet, for instance, its homage to court etiquette and formal bows. But the form, a lived tradition, has transformed and blossomed over time and continues to evolve today.

Where the Genres Meet: Minuet and Grand Bélé

As someone who has read extensively about the minuet and practiced the stepping and spatial patterns of the dance for over twenty years, I felt a visceral connection when learning some of the grand bélé steps with Kieron Sargeant. What struck me were the physical commonalities: the embodiment of “grace” in action, the use of repetitive rhythmic patterns, gracious gestures, and the gentle pulse of sinking and rising with each step pattern.

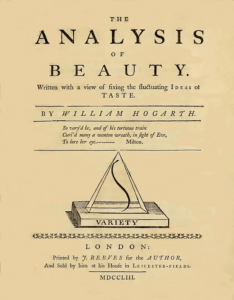

Conceptually, the connective tissue lies in William Hogarth’s explanation and description of the “line of beauty” in his treatise An Analysis of Beauty from 1753. According to Hogarth, the line of beauty is not composed of sharp, staccato, angles and rhythms –it is an undulating, legato, curvilinear pathway that spirals with pleasing variety, like the ebb and flow of the ocean. In both dance forms, the viewer can see the gentle pulse of the rhythm and melody in the bodies of the dancers, as if the whole body is riding a gentle wave for the entirety of the dance.

In the minuet and grand bélé, the undulating pathways are also multi-planar. For the minuet, these pathways lie in the basic minuet step which consists of soft bends and rises. The cadence of the step ebbs and flows, like the tides (step on “1”, hold “2”, “3”, then surge forward “4, 5, 6”). The tracts in space that the dancers trace along the floor are also serpentine and circular (see the minuet video for the entire dance).

So, too, in the grand bélé, there are circular pathways, more like those of an English country dance or quadrille, and soft, undulating gestures of the wrists, heads, and legs. The skirts of the ladies, open and close, billow and fall with the turning patterns, and the torso bends from side to side in a gentle rocking motion.

Where the Dances Diverge

The Secular and the Sacred

The minuet for a man and a woman was a presentational dance performed before one’s community, and to have the honor of dancing the first minuet signified that the couple were highly ranked in their society. For instance, George Washington led out many minuets during his tenure as General of the Continental Army and also, as President of the United States.

The grand bélé, however, serves secular and sacred purposes in the community, again a reflection of Africanist and European influences. It can be choreographed and performed at heritage festivals in Trinidad as a celebration of culture. But it can also play a part in a community’s sacred rituals. The ritualistic form draws upon various Africanist traditions of the enslaved, requiring purification of the space, instruments, and instrumentalists (refer to this lecture for more information on the bélé’s sacred purpose).

Figures, or Patterns in Space

The grand bélé employs a broader range of groupings and patterns compared to the minuet for a man and woman. It shares more in common with European quadrille or cotillion sets. However, according to Emelda Lynch Griffith, President of the National Dance Association of Trinidad and Tobago, there are no set figures per se. In quadrille versions, men and women pair off, usually in couples of four but the dance can employ as many couples as will dance, as long as there are pairs of partners.

Costuming

Both dances require(d) elaborate costuming involving layers of fabric and formal attire.

In Figure 4, the engraving captures a formal ball at St. James’ palace in London. The couple are dancing a minuet in full court dress, including wide hoops for the lady. This style of dress was also required by local assemblies. For instance, the rules listed in the “The New Bath Guide” of 1769 required “That Ladies, who dance Minuets, be dressed in a full Suit of clothes, or a full-trimmed Sack, with Lappets and large Hoops, such as are usually worn at St James’s.“ And, “That the Gentlemen who dance Minuets, do wear a full-trimmed Suit of Clothes, or French Frock, Hair or Wig dressed with a Bag.” The rules go on to state that no lady would be allowed to dance in hoops for the country dances, so clearly a costume change was required of those who wish to partake in that communal fun; there was no room for wide hoop skirts in a longways set of dancers!

Yale University, The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Reflecting 19th-century European fashion, the man’s dress is a more streamlined silhouette, trousers and long sleeved shirts, white or coloured, with brightly coloured scarves around their necks and waists.

The Music

In the 18th century, there were sung and danced minuets, but the meter never changed. Only instrumental minuets were danced to in the ballroom, and, despite the lack of rhythmic variation, there was variety in the character of each minuet composition; some are very grand and regal while others feel more tender and sweet. Ignatius Sancho’s minuets each have a distinct character and were written for harpsichord, mandolin, and flute. Unusually, five of them include notated parts for the french horn, not a typical dance band instrument in the 18th century. In our recording, we only used violin accompaniment, which was the typical accompaniment in dancing lessons.

Bélé music, on the other hand, offers much more variety in instrumentation, with each group composing its own drum and song rhythms designed to inspire and draw the dancers into the dance. Traditionally, there are three traditional skin drums: cutter, fuller, and bass and improvisation is practiced. The instruments used in the bélé filmed above include bass drum, cutter, fuller, flute, harmonica and voice and the composition fuses Africanist and European rhythms.

Conclusion

While Trinidadian grand bélé can trace some of its roots to the French minuet, its evolution has taken it to a domain of vast diversity and dynamism. Unlike the up-right minuet, the grand bélé embraces akimbo stances, off-centered leans, and showcases layers of rhythmic intricacy. Like numerous versions of the bélé, it carries retentions from the Congo basin and echoes social dances from regions like Angola. Indeed, in more Africanist and social versions of bélé, one can observe nuances like the thighs and belly coming together, reminiscent of the Angolan Semba.

Both the minuet and grand bélé have been passed down through the generations in some form or another. While the bélé thrives in the realm of possibility and creativity, the minuet experienced gaps in transmission, leading to an early 20th- century portrayal as a dainty relic of rococo costuming and manners. However contemporary research is revealing rich and complex forms of the minuet as it was danced in the time of Ignatius Sancho, a practice that can be revived and re-imagined by today’s dancers.

In the grand tapestry of dance, where bélé and minuet intersect, is their shared aesthetic values- their mutual reverence for beauty, line, and shape.

Embodied Dance Historian Tip: Always go to the source!

____________________________

18th Century European and American Dance Sources

A Comprehensive List of Original Sources: Library of Dance

Sources on Trinidadian bélé

The Bele Lecture/ Demonstration – Emelda Lynch Griffith for Kieron Dwayne Sargeant Lecture Series – Dancing the Caribbean Histories, Ethnographies and Geographies.

Molly Ahye’s, Golden Heritage -The Dance of Trinidad and Tobago, 1978

Daniel, Yvonne. Caribbean and Atlantic Diaspora Dance : Igniting Citizenship. University of Illinois Press, 2011.

Manual, Peter, Editor. Creolizing Contredance in the Caribbean. Temple University Press. 2009

Sloat, Susanna, and Susanna Sloat. Caribbean Dance from Abakuá to Zouk : How Movement Shapes Identity. University Press of Florida, 2002.

Information on Images of Enslaved Africans

Newspaper Accounts and Advertisements

The Performing Arts in Colonial American Newspapers, 1690-1783

The Digital Library of the Caribbean

Further Historical Reading

Miller Monica L. Slaves to Fashion : Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity. Duke University Press 2010.