The Anti-Slavery Legacy of the Sancho-Sterne Correspondence in the Periodical Press

by Alex Solomon

Rutgers University

alexgsolomon@gmail.com

As you know if you are browsing this site, Ignatius Sancho did more than write letters. His epistolary career is, nonetheless, central to his cultural legacy. The 1782 publication of his collected letters, with a brief biography appended, would be the basis for most general knowledge about him until quite recently. Sancho’s 1766 letter to the English novelist Laurence Sterne is certainly his most widely known piece of writing, and is, accordingly, the centerpiece around which his reputation as a man of letters is built; it is the most frequently excerpted segment of his published correspondence and the first—or only—piece of information mentioned about him in many records of his life and work.

Here I’ll attempt to provide a concise overview of the popularity of the Sancho-Sterne correspondence (Sancho’s first letter and Sterne’s response later in the summer of 1766) through attention to its reprinting in periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic, from the late-eighteenth through the mid-nineteenth century. In tracing this print history, I want to draw out a set of cultural dynamics that become visible only through close analysis of what publications printed the correspondence, what other material by or about Sancho or Sterne they published, how it was framed or advertised, and what sorts of material it shared space with. This deep dive through periodical archives does not bring a single, overarching narrative into view, but we can, nonetheless, recognize a subtle pattern: Sancho’s fame is at first grafted onto Sterne’s, while Sterne’s enduring legacy as an abolitionist thinker is, over time, drawn out of his association with Sancho.

In the summer of 1766, Sancho wrote to Sterne, identifying himself as a devoted fan of Tristram Shandy, the massively popular and formally innovative novel that been released over multiple volumes starting in 1759, and expressing admiration for Sterne’s earlier published sermons, including one on slavery.

He makes a humble request: “That subject, handled in your striking manner, would ease the yoke (perhaps) of many—but if only of one—Gracious God! – what a feast to a benevolent heart!” But soon after he follows up with a demand: “you cannot refuse.—Humanity must comply.”

But soon after he follows up with a demand: “you cannot refuse.—Humanity must comply.” Sterne responds warmly, claiming, “There is a strange coincidence, Sancho: I had been writing a tender tale of the sorrows of a friendless poor negro—girl, and my eyes had scarse done smarting with it, when your Letter of recommendation in behalf of so many of her brethren and sisters, came to me.”

When the ninth and final volume of Tristram Shandy was released later that year, it did include a scene featuring a poor black girl, but one outside the novel’s primary timeline, not involving any of the primary characters, and far too brief to be called a “tale.” It is genuinely unclear how exactly this scene criticizes the practice of slavery let alone advocates for its abolition.

When Tom, an’ please your honour, got to the shop, there was nobody in it, but a poor negro girl, with a bunch of white feathers slightly tied to the end of a long cane, flapping away flies—not killing them.—’Tis a pretty picture! Said my uncle Toby—she had suffered persecution, Trim, and had learnt mercy—

—She was good, an’ please your honour, from nature, as well as from hardships; and there are circumstances in the story of that poor friendless slut, that would melt a heart of stone, said Trim; and some dismal winter’s evening, when your honour is in the humour, they shall be told you with the rest of Tom’s story, for it makes a part of it—

Then do not forget, Trim, said my uncle Toby.

A negro has a soul? An’ please your honour, said the corporal (doubtingly).

I am not much versed, corporal, quoth my uncle Toby, in things of that kind; but I suppose, God would not leave him without one, any more than thee or me—

—It would be putting one sadly over the head of another, quoth the corporal.

It would so; said my uncle Toby. Why then, an’ please your honour, is a black wench to be used worse than a white one?

I can give no reason, said my uncle Toby—

—Only, cried the corporal, shaking his head, because she has no one to stand up for her –

—’Tis that very thing, Trim, quoth my uncle Toby,—which recommends her to protection—and her brethren with her; ’tis the fortune of war which has put the whip into our hands now—where it may be hereafter, heaven knows!—but be it where it will, the brave, Trim! will not use it unkindly.

—God forbid, said the corporal.

Amen, responded my uncle Toby, laying his hand upon his heart.)

Timeline:

Timeline:

1766: Sancho-Sterne Correspondence

1767: Publication of Tristram Shandy, vol. 9

1768: Death of Sterne

1775: Publication of Letters of the Late Rev. Mr. Laurence Sterne

1780: Death of Sancho

1782: Publication of Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African

Sterne died within two years of responding to Sancho’s letter, and his correspondence was first published in 1775; here the exchange emerges as an item of particular curiosity. It is mentioned in just about every review of the volume and is often excerpted on its own, with or without any advertisement or mention of the larger volume.

The public interest in this correspondence was, without a doubt, a significant factor in Frances Crewe’s effort to publish Sancho’s letters. This association with Sterne put Sancho on the literary-cultural map, certainly, but, as I will show, the correspondence also sustained, if not created, Sterne’s public image as an anti-slavery figure.

From 1775, the excerpted exchange was everywhere, first in the British press and eventually in the American press as well. We could catalog dozens, maybe hundreds of appearances of the correspondence in different newspapers and journals. The letters were republished in The Gentleman’s Magazine, Sentimental Magazine, The Scots Magazine, The European Magazine and London Review, Weekly Miscellany, The Monthly Miscellany, and Town and Country Magazine, just to offer a small sample. These were mostly general interest journals, some more focused on politics and current events, some more on literature and culture; some, like Town and Country, specialized in salacious anecdotes and gossip. While it is difficult for twenty-first century readers to recognize the allegiances and interests behind each of these publications, the different ways in which they “packaged” the Sancho-Sterne correspondence is itself revelatory of the assumed readers’ sensibilities. Looking at the list below (Figure 1), we can discern a significant difference, for instance, between, “Letter from Ignatius Sancho, a free Black in London, to the late Rev. Mr. Sterne” and “A LETTER from a NEGROE to the late MR. STERNE” (this item title appears in the February 9, 1778 issue of Weekly Miscellany, where the name “Sancho” only appears in the text of Sterne’s letter).

Figure 1. Contents of the New London Magazine (June 1792) including the Sancho-Sterne correspondence and Contents of the Weekly Miscellany (October 1773) including the Sancho-Sterne correspondence.

Examination of the tables of contents of the publications that reprinted the correspondence can also be quite illuminating. The range of literary and cultural contexts in which it appeared is simply immense. The letters between Sancho and Sterne could be wedged between pieces of amatory fiction, general history articles for bourgeois readers, or even essays defending the slave economy. Much like modern media consumers, eighteenth-century readers could move idly from sentimental contemplation of the atrocities that enable their quality of life to analysis of stock and commodity prices. Here, for example, is the table of contents for an issue of the New London Magazine in June 1792 (Figure 2). The list of topics that this issue contains is extremely wide.

The Sancho Sterne letters thus constitute a viral text with a wide popular appeal, reaching a massive readership: men and women, cultural elite and working class, conservative and progressive, etc. In late eighteenth-century British publications, the correspondence implicitly traffics in anti-slavery sentiments but is hardly bound to that political function. On the other side of the Atlantic, the Sancho-Sterne correspondence is not quite as ubiquitous, but mentions of these men in connection with one another occur sporadically across the first half of the nineteenth century. The prevailing narrative, particularly in American abolitionist presses, is that Sterne’s response to Sancho, and his overtures at friendship, constitute an ideal form of benevolence. An 1846 issue of Liberator, a major abolitionist paper, takes another paper’s writer to task for not acknowledging Sterne’s explicit engagement with the tragedy of slavery (though, in reference to a passage, quoted below, that does not actually refer to the Atlantic slave trade). In an 1850 issue, Frederick Douglass’s paper, The North Star, briefly cites the correspondence to highlight Sterne’s claim of kinship, as shown in Figure 3:

This dynamic is well encapsulated by the respective treatments of Sancho and Sterne in Freedom’s Journal, the first Black American periodical. While, over the course of the journal’s two-year print run, Sancho is only very briefly mentioned among a list of notable Black historical figures taken from the writings of the French abolitionist Abbé Gregoire, a whole passage from Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey—a passage some critics think was inspired by Sancho—appears on the front page of an 1827 issue (Figure 4):

The text of this passage is as follows:

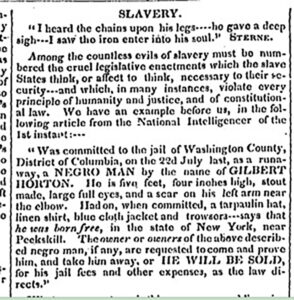

The bird on his cage pursued me into my room: I sat down close to my table, and leaning my head upon my hand, I began to figure to myself the miseries of confinement. I was in a right frame for it, and so I gave full scope to my imagination. I was going to begin with the millions of my fellow creatures born to no inheritance but slavery; but finding however affecting the picture was, that I could not bring it near and that the multitude of sad groupes in it did but distract me —– I took a single captive, and having first shut him up in a dungeon, I then looked through the twilight of his grated door to take his picture. I beheld his body half wasted away with long expectation and confinement, and felt what kind of sickness of the heart it was which arises from hope deferred. Upon looking nearer, I saw him, pale and feverish; in thirty years the western breeze had not once fanned his blood – he had seen no sun, no moon, in all that time – nor had the voice of friend or kinsman breathed through his lattice: his children —- But here my heart began to bleed – and I was forced to go on with another part of the portrait. He was sitting upon the ground, upon a little straw, in the farthest corner of his dungeon, which was alternately his chair and bed: a little calendar of small sticks was laid at the head, notched all over with the dismal days and nights he had passed there – he had one of those little sticks in his hand, and with a rusty nail he was etching another day of misery to add to the heap. As I darkened the little light he had, he lifted up a hopeless eye towards the door, then cast it down -shook his head, and went on his work of affliction. I heard his chains upon his legs, as he turned his body to lay his little stick upon the bundle. He gave a deep sigh – I saw the iron enter into his soul – I burst into tears – I could not sustain the picture of confinement which my fancy had drawn.)

This passage does not condemn slavery in any straightforward manner, but rather conveys Sterne’s narrator’s solipsistic and thoroughly ambivalent attitudes regarding the issue—specifically his inability to hold the physical realities of slavery in his mind. The content, in other words, is not itself the strongest evidence of Sterne’s actual antislavery commitments. It appears to be, rather, the consistent reprinting of Sterne’s words in abolitionist contexts that established his credentials in posterity (Figures 5 and 6).

The mediatic fates of Sancho and Sterne are in many ways emblematic of the wider pattern of historical erasure through which the role of Black activists in the achievement of abolition in the United States and across the British Empire has received less public attention than that of a select group of white philanthropists. Sancho’s gradual marginalization from a literary historical and political narrative that he himself initiated can hardly be blamed, posthumously, on Sterne. And there is of course great value in continued scholarly attention to the ways in which phenomena like literary celebrity and sentimentalism advanced antislavery discourse. Nonetheless, the fate of Sancho’s letter to Sterne ultimately provides the strongest evidence for the necessity of projects that give proper attention to any and every other aspect of Sancho’s life and career.