Music Making With Sancho’s Daughters

By Julia Hamilton and Ithaca College

jhamilton4@ithaca.edu

The Sancho home on Charles Street in Westminster must have been filled with music. Ignatius Sancho was so well pleased with eighty-six of his own compositions that he had them published in five books of music. He was also a proud and loving father who was heavily involved in his children’s lives. His letters and musical publications, along with a contemporary account of his family life, provide some insights into the music making of his children—and particularly his daughters.

Ignatius and Ann Sancho had seven or nine children. Vincent Carretta’s authoritative edition of Sancho’s letters provides the names of seven children: Frances (1761–1815), Ann Alice (a.k.a. Mary Ann, 1763–1805), Elizabeth (1766–1837), Jonathan (1768–1770), Lydia (1771–1776), Catherine (1773-1779), and William (1775–1810). Recent research at Northeastern University from a team led by Nicole Aljoe and Oliver Ayers suggests that there may in fact have been eight Sancho children. According to their “Ignatius Sancho’s London” website, Ann Alice died young, living only until 1766—and she was a distinct person from her older sister, Mary Ann (1759–1805).

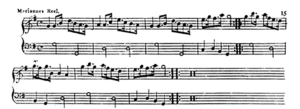

Regardless of the total number of children in the Sancho family, there is some evidence from Ignatius Sancho’s published musical compositions to suggest that he shared his music with his children when they were young. His second volume of dance pieces (published ca. 1770) contains a tune called “Mariannes Reel” (Figure 1).

Depending on the date of her birth, Mary Ann would have been around 7 or 11 years old at the time. Perhaps Ignatius wrote this reel in honor of his daughter’s burgeoning love of music and dancing. Perhaps Mary Ann even collaborated on its composition while she was in her early days of her music education. We know from Sancho’s letters that he wrote music with specific friends and family members in mind. He asked these friends to play through and collaborate on his compositions. In a letter from 1777, for example, he asks his friend to “make Jack play” a dance tune, which he seems to have enclosed in the letter. He also requests they “contrive a figure”—that is, come up with the dance steps for this tune. Additionally, Sancho set to music poems written by his friends: his letter from September 20, 1777 alludes to the process of setting a friend’s poem to music. He writes: “Well, I have critically examined thy song–some parts I like well…I will certainly attempt giving it a tune–such as I can–the first leisure–but it must undergo some little pruning when we meet.”His published song “Friendship Source of Joy” was a setting of a poem written by a young Lady. In light of these friendly collaborations, it seems possible that Sancho incorporated his daughter Mary Ann’s ideas and/or preferences in some way in “Mariannes Reel.”

Another possible reference to Sancho’s children in his musical compositions can be found in the titles of dances in Sancho’s first book of dances from ca. 1767. This book includes several dance titles that seem to evoke fairy tales or exoticized travel narratives: “The Fairy Tales,” “The Carravan,” “The Dwarves,” “The Matadors,” and “The Sword Knott.” Sancho is known to have created literary themes in his books of music: his collection of songs features three Shakespearean texts and his book of Cotillions &c. from 1775 includes numerous references to the works of Laurence Sterne. So it is possible that these references to fairy tales reflect the types of stories he was reading to his young children when Mary Ann was 8 or 4 years old, Frances was 6, and Elizabeth was 1.

In addition to sharing his own music with his children, Sancho took them to hear top-notch professional performances when they were in their tween and teen years. On August 21, 1777, Ignatius took Mary Ann (aged either 18 or 14) and Elizabeth (aged 11) to see Henry IV Part I at the Haymarket Theater. In a letter from August 25th, he writes: “I had an order from Mr H(enderson) on Thursday night to see him do Falstaff—I put some money to it, and took Mary and Betsy with me—it was Betty’s first affair—and she enjoyed it in truth.” On August 26th, he took his older children to hear a concert at the Vauxhall pleasure gardens. In a letter from August 27th, he writes, seemingly reporting on himself: “I know a man who delights to make every one he can happy—that same man treated some honest girls with expences for a Vauxhall evening.—If you should happen to know him—you may tell him from me—that last night—three great girls—a boy—and a fat old fellow—were as happy and pleas’d as a fine evening—fine place—good songs—much company—and good music—could make them.—Heaven and Earth!—how happy, how delighted were the girls!” Likely, the “three great girls” were Mary Ann (aged 18 or 14), Frances (aged 16), and Elizabeth (aged 11). Alternatively, it may be that Ignatius brought one of his daughters and a few of her friends; we know from a letter describing Mary Ann’s sixteenth (or twentieth) birthday party in September 1779 that she had a few friends who came along to the house for celebrations.

Though there are no direct references to the children’s domestic music making in Sancho’s letters, three of the Sancho daughters reached their teens and adult years: Mary Ann (d. 1805), Frances (d. 1815), and Elizabeth (d. 1837). These daughters are very likely to have engaged in the domestic music-making practices that were expected of girls and women in the eighteenth century. Moreover, we do have one contemporary source that describes their musical activities in 1784, four years after their father died. Elkanah Watson, an American banker and agriculturalist who had completed an apprenticeship with a Rhode Island-based slave trader, toured London in 1784. His memoirs, published in 1856, include an account of a visit he made to the Sancho shop and home on Charles Street back in 1784. The account is marred with racism and colorism—the author is fixated on describing the complexions and racial backgrounds of the people he encounters—but it is notable in that the author names and interrogates his own racial prejudices. These include preconceived notions about Black women, to whom Watson had apparently never before given respect. The source is also especially important because it confirms that at least one of Sancho’s daughters played the harpsichord. Watson writes that in a “neat back parlor” beyond the grocery shop, he heard an impromptu domestic concert:

One of the daughters, when we entered, was sitting at a harpsichord, and a white gentleman, in appearance, singing with her in concert. One or two other white persons came in, and we spent a pleasant hour in conversation, interspersed with singing and music, and yielded to the females the same respectful attention that we should have extended to white ladies.—‘And why not?’ exclaims the philanthropist. The potent influence of prejudice cannot readily be subdued. A family of cultivated Africans, marked by elevated and refined feelings, was a spectacle I had never before witnessed.

Watson’s account speaks to the intersecting prejudices the Sancho women would have faced as Black women living in eighteenth-century London. While they were expected to make music as women, they were understood by some to be “unrefined” and therefore unable to engage in polite music making. This was a similar set of prejudices Sancho was working against when he published music as “An African,” though his daughters faced additional societal pressures as women.

To my knowledge, none of the Sancho family music collection exists today, but it is likely that the musical party in 1784 featured the same sorts of music that can be found in extant contemporary British women’s collections. These include Vauxhall songs, opera arias, sets of songs, and keyboard pieces, including dance music like Ignatius Sancho’s. One tantalizing question I have is whether the Sancho women would have purchased and performed the abolitionist songs that became popular with white women in the later 1780s through the 1830s. Several of these songs focused on the figure of the enslaved girl or mother, such as William Carnaby’s “The Negro Girl” (ca. 1801), John Ross’s “The Negro Mother” (1802), and S. Ball’s “The Negro Girl’s Rescue” (1806).27 Would Mary Ann, Frances, and Elizabeth have found this music to be politically powerful and emotionally affecting, as their white contemporaries did? Would they have performed the role of the enslaved woman in song, finding power in the ability to represent Black womanhood instead of allowing white singers to take on this role? Or would they have objected to the patronizing tone of these songs? Might they have held mixed feelings about them? The few extant letters that were written by Elizabeth Sancho in the 1810s are silent on these questions of music making and abolitionism. They are primarily concerned with Elizabeth’s finances and relationships with her patrons in the years after all her immediate family members had died. Even so, it is worth considering how Mary Ann, Frances, and Elizabeth Sancho would have engaged in music making in this period of heightened public discussion of slavery, when Black women faced intersecting and conflicting societal expectations of femininity and Blackness.