Ignatius Sancho and the Black Presence in Domestic and Concert and Music of the Eighteenth Century

By Rebecca Cypess

rcypess@mgsa.rutgers.edu

Ignatius Sancho stands out as one of the few Black people of the eighteenth to publish his original musical compositions, but he was certainly not alone in his musicianship. In Sancho’s London and across the eighteenth-century Black Atlantic, Black musicians created music. Those who were born in Africa brought musical traditions with them, and these traditions merged with and shaped the sounds of their new environment. Whether enslaved or free, Black people in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world used music as a means of self-expression, resistance, and the creation of community. Because music is an ephemeral art, much of that music survives only in oral tradition today.

Sancho’s birthplace is unclear—his biographer, Joseph Jekyll, claimed that he was born aboard a slave ship crossing the Middle Passage, but Sancho himself wrote that he was “born in Afric”—but he was certainly in London from a young age, and he grew up listening to the music that was made in domestic and concert settings of that city. His compositions participate in—and respond to—the genres that he heard there: he wrote social dance pieces like minuets, cotillions, and country dances, as well as songs for voice and keyboard.

In this essay, I’ll suggest ways in which Sancho’s musical compositions and his letters open the way to a wider view of Black participation in the domestic and concert repertoires of eighteenth-century London.

Ignatius Sancho stands out as one of the few Black people of the eighteenth to publish his original musical compositions, but he was certainly not alone in his musicianship. In Sancho’s London and across the eighteenth-century Black Atlantic, Black musicians created music. Those who were born in Africa brought musical traditions with them, and these traditions merged with and shaped the sounds of their new environment. Whether enslaved or free, Black people in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world used music as a means of self-expression, resistance, and the creation of community. Because music is an ephemeral art, much of that music survives only in oral tradition today.

As I have argued in this essay, one of the most striking features of Sancho’s instrumental dance music is his inclusion of parts for the French horn in five of his minuets. The French horn was primarily an instrument for professional musicians; like most brass instruments, its practices were transmitted from teacher to student as an oral tradition. Dance music, too, was mostly a matter of oral tradition, since instrumentalists knew how to elaborate on the basic melodies and formulas of dance pieces in order to keep the music going. For both these reasons, it is exceedingly uncommon to find notated horn parts in instrumental dance music from this period.

Yet many Black musicians in eighteenth-century London played the French horn. Sancho’s younger contemporary, the writer and antislavery activist Olaudah Equiano, describes learning the French horn while living in London:

We had a neighbor in the same court who taught the French horn. He used to blow it so well that I was charmed with it, and agreed with him to teach me to blow it. Accordingly he took me in hand, and began to instruct me, and I soon learned all the three parts [i.e., low, middle, and high, each of which had its own technique and performance practices]. I took great delight in blowing on this instrument, the evenings being long; and besides that I was fond of it, I did not like to be idle, and it filled up my vacant hours innocently

Indeed, other Black musicians in London and in the Americas learned to play the horn, often so that they could play at ceremonies or to accompany dancing or the hunt.(See this essay, as well as my longer article on the subject and Figure 1, for further evidence.) By including notated parts for the French horn in his dance music—parts that were rarely, if ever, included in publications of dance music for small ensembles by other composers—Sancho points the way to the association of Black musicians with the French horn. Even as he records his own musicianship in print, he points beyond himself, apparently expressing affiliation with other Black musicians whose performances on the horn are lost to history because they were never notated.

Moreover, as noted in the essays on this website on Sancho and dance, Sancho’s dance compositions would have been used in a variety of settings, including all-white dances at homes such as that of the Montagu family, and all-Black balls that were known to take place in London. Sancho’s work in the genres of domestic dance open those genres as a dialectic space available to both Black and white musicians and dancers.

Sancho’s letters show how deeply he was embedded in the musical environment of his time, and they suggest additional avenues by which Black musicians cultivated and displayed their musicianship. In a letter dated April 9, 1778, Sancho describes obtaining tickets to a benefit concert from Felice Giardini, one of the leading violinists in London at the time: “the ticket was a present from the great Giardini—to the lowly Sancho.” Giardini was a leading figure on London’s concert stage. That Sancho knew him personally, and that Giardini gifted a concert ticket to Sancho, suggest that Sancho was involved extensively in the wider musical world and knew many of the leading figures in it. It also seeks possible that Sancho, a literate and well-trained musician, knew and played Giardini’s compositions.

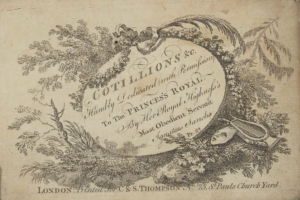

If Sancho knew and played Giardini’s compositions, he probably knew and played works by other leading composers of London, including Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel, as well as the works of George Frideric Handel, which were especially loved and promoted by King George III. After all, Sancho’s patron, George Brudenell, first Duke of Montagu of the Second Creation, served as governor to the king’s eldest sons, the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York. Evidence that Sancho himself was connected to the royal circle of George III and Queen Charlotte lies in the fact that he dedicated his Cotillions of 1776 (Figure 2) to the Princess Royal, their eldest daughter, who was only 10 years old at the time.

Soubise is a more complicated character. Having grown up in the home of the Duchess of Queensbury, Soubise is reported to have assumed the affectations of a “fop”—a characterization imposed on him by white observers, and hardly an objective one—and for this, he and the Duchess were mocked in London society. Sancho’s letters to Soubise seem to chide him for his behavior, but Sancho also provides Soubise with advice that he thought would be useful in helping him to navigate the complexities of his Black identity in British society. In 1830, the fencing master Henry Angelo, son of the fencing master who instructed Soubise, included accounts of Soubise in his memoirs. Angelo recalls that Soubise “played upon the violin with considerable taste, composed several musical pieces in the Italian style, and sang them with a comic humour that would have fitted him for a primo buffo [leading comic role] at the Opera-house.”

Moreover, Soubise was a “favourite performer at the Vauxhall pleasure gardens” who “always won mighty applause and an encore for his comic opera rendering of a popular ditty called ‘As now my bloom comes on apace the girls begin to tease me.’” When this sexually suggestive song was published in a periodical in 1772, it was described as “sung by Miss Jameson, at Vauxhall” (Figure 3). Thus, like so many instances of Black musicianship, Soubise’s performances were omitted from this published record. Nevertheless, the fact that he is reported to have sung this song, played the violin, and even composed “several musical pieces in the Italian style” opens up the repertoire of Italianate sonatas and the hundreds of surviving Vauxhall songs as possible vehicles for the performance of Black musicianship and musical agency in Sancho’s London.

Sancho was also involved in domestic music and dance within his own social network, as shown in his letters. He wrote to his (white) friend John Meheux in September 1777: ‘I have critically examined thy song—some parts I like well. . . . I will certainly attempt giving it a tune—such as I can—the first leisure—but it must undergo some little pruning when we meet.” This excerpt suggests that his skill at composition was in demand within his own social circle, a notion echoed in his letter of November 5, 1777, to Mrs Cocksedge: “the little dance (which I like because I made it)—I humbly beg you will make Jack play—and amongst you contrive a figure” (i.e., make up a dance to go with Sancho’s tune).

Olaudah Equiano’s autobiography provides further evidence of music-making across the Black Atlantic. He describes the Igbo nation of Africa as “almost a nation of dancers, musicians, and poets,” and he recalls the “many musical instruments” of his people. Traveling around the Atlantic world as a sailor—first enslaved and later as a free person, though always at risk—Equiano heard the sounds of other Black people and of the Christian, predominantly white populations that he encountered. In the Caribbean, he describes having participated in “free dances, as they are called, with some of my countrymen,” suggesting that he joined in their music-making and dancing.

What the music for such dances might have sounded like in the eighteenth century must remain a source of speculation, as it was passed down through oral tradition. However, the contributions by Caroline Copeland and Kieron Sargeant to this project note significant points of overlap between dance practices of British courtly circles and those transmitted from one generation to the next among Black communities of the Caribbean. Observers from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries —some white and others Black—sometimes used Western musical notation to record fragments of Black African song, but the precise status of these notated pieces as historical evidence is unclear. Any time non-Western practices are notated using a Western system of notation, the system of notation introduces challenges and constraints; such notated fragments can never be taken at face-value as “objective” representations of a musical truth.

At the same time, displaying his ability to “code-switch,” Equiano shows how deeply embedded he was in the British musical styles of his time, although he left no record of having been able to read or write in Western musical notation. For example, after describing his conversion to Christianity, Equiano includes 28 stanzas of “miscellaneous verses, or reflections on the state of my mind during my first convictions; of the necessity of believing the truth, and experiencing the inestimable benefits of Christianity.” The poem is in iambic tetrameter—that is, it has four strong syllables per line—giving it a lilting meter that was easily set to music.

Well may I say my life has been

One scene of sorrow and of pain;

From early days I griefs have known,

And as I grew my griefs have grown.

[…]

Yet here, ’midst blackest clouds confin’d

A beam from Christ, the day-star, shin’d;

Surely, thought I, if Jesus please,

He can at once sign my release.

Indeed, the poem is in the style of a hymn and could easily have been sung to any number of hymn tunes that were in use in Anglican and Methodist churches of England and the early United States. Equiano’s poem serves as a call to communal action: by inspiring his readers to sing of repentance and shared humanity, he tapped into their spiritual natures as a source of inspiration for antislavery activism. Communal music could serve to galvanize an antislavery public.

Ignatius Sancho commented on the poetry of another Black writer, Phyllis Wheatley, who had been kidnapped as a girl of around seven years old from her home on the coast of West Africa and enslaved by the Boston businessman John Wheatley. When Wheatley published her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773), Sancho received a copy from one “Mr. F.,” whom Vincent Carretta has identified as “probably Jabez Fisher (1717–1806) of Philadelphia.” In responding to Mr. F., Sancho wrote,

Phyllis’s poems do credit to nature—and put art—merely as art—to the blush.—It reflects nothing either to the glory or generosity of her master—if she is still his slave—except he glories in the low vanity of having in his wanton power a mind animated by Heaven—a genius superior to himself—the list of splendid—titled—learned names, in confirmation of her being the real authoress.—alas! Shews how very poor the acquisition of wealth and knowledge are—without generosity—feeling—and humanity.—These good great folks—all know—and perhaps admired—nay, praised Genius in bondage—and then, like the Priests and Levites in sacred writ, passed by—not one good Samaritan amongst them.

It is no coincidence that Sancho read and commented on Wheatley’s poetry. Even as he cultivated his connections with the white elite and the white artistic community, Sancho embedded himself in a community of Black artists, writers, and musicians.